What’s the best argument for God?

It was the Fifth of September, 1973, and I had just moved up to Junior Class at Sidcup Hill Primary School. I had missed the first day of school because I was ill, so I missed the instructions for how things would be different for us grown-up children.

English schools in those days said the Lord’s Prayer every morning and sang a few hymns, too. I had just closed my eyes and put my palms together to pray when Graham grabbed my hands.

Our Father,

Who art in heaven,

Hallowed be thy name.

I opened my eyes, and Graham was forcing my fingers to intertwine. He shook his head as if to upbraid me for my ignorance.

“We don’t pray like that now. We are not infants.

That was the moment when I stopped believing in God. It all seemed so silly. I still enjoyed the hymns and the Lord’s Prayer. I just didn’t believe that the words were true.

I still enjoy going to church. In fact, I just went to Bristol Cathedral on Easter Sunday. I can appreciate my country’s culture without believing that Beowulf walked the earth or St George killed the dragon. I can enjoy going to church, too.

English atheists are far more relaxed about religion than their American cousins. It’s all very relaxed over here, and no one even cares whether you are a believer or not. Growing up in England in the 70s and later as an adult in the 80s, there was very little tension between Christians and atheists. As far as I knew, very few of my friends and acquaintances were Christian but, even so, practically everyone went to church when the occasion called for it and everyone said The Lord’s Prayer in school assembly every morning.

I read a Substack article last week asking atheists which argument for God seems most persuasive, even if it doesn’t entirely persuade them. The most popular argument by far is the fine-tuning argument.

Scientists say that there are a bunch of constants that determine the shape of our universe. If the gravitational constant were a bit stronger, our stars would all be sucked back into a singularity. If it were a bit weaker, they’d all fly off into infinity. Either way, there would be no Earth — and no humans. It is a lucky coincidence that these five or six constants are all just right because if they were a little different, we wouldn’t be here. According to the fine-tuning argument, it’s unlikely that all these constants could be just right all on their own, so we must assume that God did it.

I’ve never been even remotely tempted by the fine-tuning argument. If it’s unlikely that the constants came about on their own, it’s just as unlikely that God came about on His own to set them. And who said they came about at all? Maybe they just are.

The most convincing argument for me is the Watchmaker Argument.

In the watchmaker argument, William Paley asks us to imagine walking across a heath. If we come across a stone, we can imagine it having been made by the weather — or perhaps it had been there forever. But if we come across a watch on the heath, the watch’s complexity forces us to assume the watch was created by a watchmaker. In the same way, an elephant or an octopus is too complex to have been created by accident and must have been created by a creator. They must have been created by God.

I am quite comfortable with the idea that elephants and octopuses share a common ancestor and that they were all created by evolution, but what about the citric acid cycle?

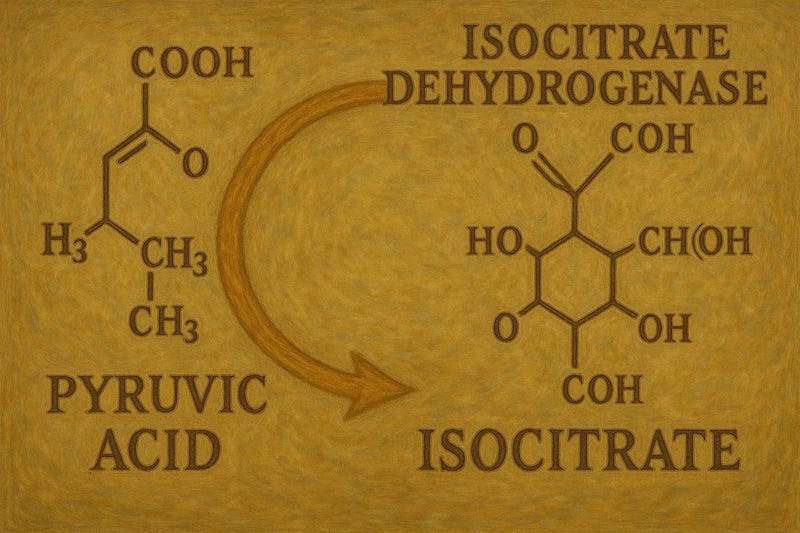

The citric acid cycle has eight enzymes that cooperate to turn pyruvic acid into carbon dioxide and water. It’s how you make energy. Don’t tell me the citric acid cycle came about by accident.

Also, my brain has 80 billion neurons. Perhaps octopuses can evolve without a grand designer, but how do all those little neurons floating around inside my brain organise themselves into my temporal lobe and my frontal lobe, separated by my Sylvian fissure, all on their own? That doesn’t seem likely to me. There has to be someone supervising that.

I’m not entirely persuaded by the argument from design. Just like the fine-tuning argument, anything that seems unlikely in our complicated bodies seems even more unlikely to have come from an omnipotent body-maker. And where did He come from in the first place?

Even if we believe in a god who is outside of space of time, how do we get from there to the Christian God? I’d guess that our idea of God evolved in the other direction.

Socrates was executed by the Athenians for disrespecting the gods, but I’d bet that neither Socrates nor the Athenians who were so offended had ever met an actual god. They were probably relying on memories of Homer’s gods from a thousand years before. Eventually, the philosophers realised that those stories weren’t literally true, but they couldn’t just throw them out. They needed new stories to take their place.

Epicurus’s gods were not like Homer’s gods. They were remote beings who were not interested in human affairs. Plato’s God wasn’t like Homer’s either. Plato’s God was the transcendent source of all that is good, but outside of human understanding. Thomas Aquinas knitted together the God of the Philosophers with the Christian God and considered God to be the ground of all being. But would it have occurred to him to describe this transcendental God if it were not for the 2,000 years of Bible stories that came before?

Would philosophers have come up with these abstract deities if they hadn’t started with deities who walked on the earth?