How much do you want to know?

I made a new cancer friend on Facebook this week. I happened to mention that I have been doing a lot of research on my tumour type and my friend said

“I would say not to do your own research as it will freak you out.”

I understand that research makes many people anxious, especially if the first thing they go looking for is survival stats. Some people with cancer would rather put themselves in the hands of their medical team and get on with their lives. Other people prefer to know as much as they can about their situation. You should choose the approach that works best for you.

“So I’m just thinking it is better to just try to not research everything and trust them.”

My friend thinks it is irresponsible to search for information on the internet because I have no medical training and if I just google blindly, the information I find is likely to be misleading and will scare me. I find that the opposite is true.

Though it’s easy to fall for confirmation bias and to find articles that agree with what you already believe, it’s also easy to look for information that challenges your beliefs and helps you synthesize an opinion that you can ask your oncologist or surgeon about. I do agree that it’s a bad idea to google blindly though.

“But you don’t really know what you are looking for.”

When you first start looking for information about cancer, start with the sources intended for cancer newbies. The brain tumour charities have some excellent information for newbies, as do the NHS and sources like Mayo Clinic and Macmillan but, eventually, you’ll want to look for more detail and more evidence.

The newbie guides might tell you that there are several kinds of glioma, for example, and that you need a biopsy to know whether your tumour is a glioblastoma, an astrocytoma, an oligodendroglioma or something else. You can google oligodendroglioma or astrocytoma to find out more about that.

Before long, you’ll be looking up terms like diffuse low-grade glioma and finding studies about the various treatments for your kind of tumour. When you have a better understanding, you’ll be able to ask good questions of your medical team and better understand their answers.

At the start of your research, there will be lots of strange terms that can be overwhelming. What is a 1p19q codeletion? Why does it matter whether my tumour’s IDH gene is mutated or wild-type? If you start to get overwhelmed — or if an article is just too confusing — put it to one side and come back to it when you know more. Remember: the purpose of your research is not to find all the answers; it’s to help you ask better questions of your oncologist and to understand the answers that they give you.

Don’t buy the snake Oil

There is a lot of bad information on the internet and there is plenty of snake oil for sale. There are sites that tell you their special diet will cure your cancer or amazing medicine derived from marijuana oil is better than the approved treatments. These sites never have supporting evidence and their recommendations are never backed up by reputable sources like PubMed. A lot of these sites begin with a rant about how the health industry tries to suppress The Truth About Cancer and they end with a special offer to buy some snake oil. You should skip those. Don’t buy the snake oil.

Some of these sites can sound quite plausible. Here’s an example.

The prevailing theory of cancer in the medical world is that cancer is caused by genetic mutations that cause uncontrolled growth. But there is a competing theory — the metabolic theory of cancer — that cancer is caused by a metabolic malfunction which, in turn, causes genetic changes in cancer cells. As a result of this malfunction, your cancer cells lose the ability to metabolise lipids so switching to a Keto diet will limit the growth of your cancer. A simplified version of this theory that you may have heard is that ‘sugar feeds your cancer’. There was a clinical trial that tried to determine the effect of a Keto diet on glioblastoma but the results were inconclusive.

If you find a treatment or lifestyle change that sounds useful, you should check with your medical team. I asked my neurosurgeon whether the Keto diet would do me any good and he said “You can try the Keto diet if you like, but it won’t do any good.”

I am glad I asked. I didn’t want to do the Keto diet anyway.

“I trust my oncologist that he knows what is best for me.”

I trust my oncologist too — and my neurosurgeon — but I trust them even more when I understand the research behind their recommendations. My neurosurgeon recommended that I have surgery to remove my tumour but there are several papers that say that the benefits of resection are questionable in a diffuse low-grade glioma (dLGG) and the possibility of neurological deficits is high.

The benefits of resection increase with the percentage of the tumour that the surgeon is able to remove. If the surgeon can remove 100% of your tumour, your survival prospects are better but the benefits drop off rapidly with less than 80% resection.

I asked my neurosurgeon…

Me: “How much of my tumour will you be able to remove?”

He: “Between 20% and 50%”.

Me: “That doesn’t seem to be a very good deal.”

He: “It is up to you whether to go ahead.”

I’m glad I did my research.

Four kinds of patient

I read an article yesterday that said patients (and the family members who care for them) will have one of four different attitudes to learning about their condition and their treatment.

1) I don’t want to know anything. Physician, heal me.

Some people find it really stressful to look anything up on the internet. If you just google blindly, you are likely to find some really bleak survival statistics and they will probably scare the shit out of you. The survival statistics mean very little, especially for brain tumours, until you understand more about your situation. Some people prefer to leave all of that to the medical team. That’s fine if it works for you.

If it makes you stressed or anxious to learn about your condition, you might be better off just living your life and letting your medical team take care of you.

2) I want to know everything.

This is me. I don’t think I can know everything but I need to know enough to ask good questions.

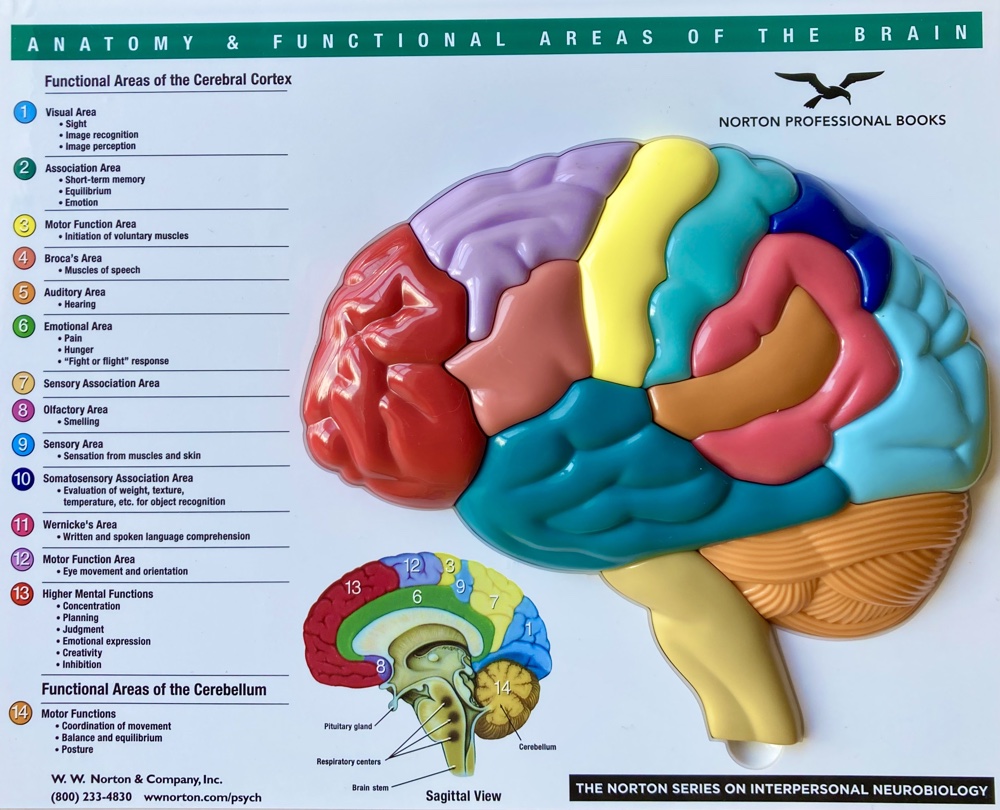

I do a lot of research about my situation. I spend a few hours every evening reading PubMed, BMJ, Science Direct and other reputable sites. I bought a copy of Principles of Neural Science and a model of a brain showing the functional areas so I have a better understanding of how my brain works and what is going wrong with it. It doesn’t freak me out at all. It gives me the confidence to deal with what is ahead.

3) I don’t care whether the treatments will work. Just keep treating me.

I think this attitude can be quite harmful. It’s one thing to accept your doctor’s opinion. It’s quite a different thing to ask for more treatment even when the treatment is unlikely to help. I think this is especially bad for elderly people who ask for, say, chemotherapy when it is more likely to make them sick than to make them better. This is definitely the time to be asking good questions of your medical team.

4) I don’t like your opinion. I want a second. And a third. And a fourth. Will someone please give me the opinion that I want?

I think this is a variation on the previous attitude. If the doc says that your preferred treatment is unlikely to help, it’s a good idea to get a second opinion. Even a third, maybe. But if they all keep telling you the same thing, it’s possible that they know what they are talking about and want what’s best for you. If you keep asking for treatment that won’t help, before you know it you’ll be flying to Mexico to get a miracle cure (NARRATOR: it probably won’t help).

Phone a friend

My tumour type is quite rare but I’ve found several people online who have the same kind of tumour as me. They are a little further along in their adventure than I am so it’s useful to compare notes with them. They are all really interested in knowing as much as they can about their situation — and each other’s — so we all benefit from sharing our research. One person in our group gets anxious from researching online but she still likes to hear information from the rest of us. We call each other when we have a big event coming up to provide advice and comfort and we debrief afterwards to check that it went well. The information we share is empowering and comforting.

Learning about your health situation can be comforting and empowering too but if research stresses you out, putting your trust in your medical team is probably a better option.