The Terrible Mr Gooden

The line between a terrific teacher and a terrible teacher is very fine. So many of the very best teachers dance along the line with fancy steps on either side, changing the lives of students fortunate to be touched by their magic or cursed by their conceit.

Mr Gooden was terrifying and a tyrant and he altered the course of my life more than anyone else.

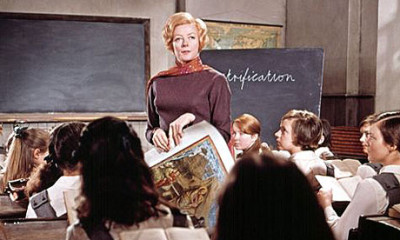

JK Rowling’s Severus Snape is the modern archetype of the terrific/terrible/terrifying teacher and Potter doesn’t know until the very end where Snape’s loyalties lie. But the tyrannical teacher par excellence is Miss Jean Brodie.

Jean Brodie: “Little girls! I am in the business of putting old heads on young shoulders, and all my pupils are the crème de la crème. Give me a girl at an impressionable age and she is mine for life.”

Maggie Smith’s terrifying teacher, long before Professors Snape and McGonegall and long, long before The Dowager Countess, was a fascist and an admirer of fascists. Miss Jean Brodie was inspired by Mussolini and Franco and inspired her girls to great heights; moulding and shaping their lives but ultimately dooming them to tragedy, sending them off to war and worse. Miss Brodie wielded charisma and conviction and certitude as weapons to inflict scorn and shame on her students. Snape too. But Mr Gooden had them both beat with charisma and conviction in abundance and he directed scorn and shame like guided missiles against a Palestinian hospital.

Mr Gooden was an evangelical Christian and ran our school’s Good News Club, a welcome refuge from a rainy winter’s lunch break. To those who didn’t know him well, he had a reputation as a ferocious disciplinarian. To those lucky enough to have him for chemistry, he was a magical storyteller, bringing his subject to life and instilling a love of science that has lasted a lifetime. Mr Gooden, the chemistry teacher would be a shoe-in for Teacher of the Year. Mr Gooden the form teacher would merit a different award entirely.

Time for a quick sidebar to explain some features of English schools for American readers. JK Rowling captured a great many features of the British Grammar School with surprising fidelity. The sorting of First Years into houses to foster competition and team spirit is spot on (give or take a Sorting Hat) and, while we didn’t have Quidditch, we did have regular inter-house rugby, cricket and track/field tournaments (Lester forever!). Ordinary and Advanced Wizarding Levels are essentially O levels and A levels—the exams you take at age 16 and 18 that determine your success or failure in life. One big difference between an English school day and my American kid’s day is that we all travelled from class to class in a herd, only occasionally breaking ranks to split up for Latin or German. Our herd travelled everywhere together including, in our case, ice skating every Sunday and the occasional trip to Margate on the train. American kids (mine at least) miss out on that camaraderie and have to work harder for their friendships. That’s one thing that my school got right. The “Form” system made it so easier to build friendships and many of my friendships from that period have lasted a lifetime.

The official name for our herd was a ‘form’. Each form had a Form Room and a Form Teacher who started and ended each day with a roll call and was responsible for the discipline and life lessons that didn’t fall under the rubric of the curriculum proper. Our Form Teacher was a prominent part of our lives (like Professor McGonegall was for Harry, Ron and Hermione) and could make those lives great or awful according to their tastes. Mr Gooden was our Form Teacher for my second and third year of grammar school (7th & 8th grade for ‘mercans).

My first day in Form 2P was filled with trepidation. Mr Gooden’s reputation as a tyrant loomed but, like many a dictator, Mr Gooden up close was quite personable; charismatic even. Our days began with laughter and inspiration and I was soon grateful for a teacher that took an active interest in our lives. We were lucky to have Mr Gooden for chemistry too and he was a born showman in the chemistry lab. How well I remember the zinc and sulphur explosion! What better introduction to molecules than the oil drop experiment?

Mr Gooden’s active interest in the form room extended to encouraging us all to donate to his special charity collection every Tuesday morning. Mr Gooden’s class was consistently the most generous in the school and he made sure that we all gave until it hurt, publicly shaming anyone who fell short. He also made sure we “volunteered” for any extra-curricular project that required work. Character-building stuff, I am sure and, considered in isolation, something to be commended. But eventually the constant pressure to “volunteer” for good deeds and give money for good causes became oppressive. But it was on disciplinary issues where Mr Gooden really crossed the line.

I’ll confess right now that I was not the most well-behaved child at Chis and Sid. I had more than the average number of detentions. The average number was close to zero but, when the headmaster announced the detentions in assembly every Tuesday and Thursday, a handful of offenders were named over and over. It was rare that the list of miscreants did not include some combination of Monroe, Harding, Winch or Lawrence. Detention began with a certificate signed by the offended teacher and counter-signed by the offender’s parents.

Other schools had a punishment called detention but it was a pale imitation of the elaborate ritual of shame that Chis and Sid inflicted on its naughtier students. Mr Gooden rarely gave out the official sanctioned punishment though. Mr Gooden’s justice was more personal; more primal. It began with a barrage of scorn for anyone who did not live up to his lofty expectations. He had a way of focussing his ray of humiliation on a single student while making every other student feel that they too had let him down. Class punishments were common but it was the private discipline that provoked the most fear.

My first private chastening came after that episode in Ms Furey’s French class. I’ll confess again that I was often the naughtiest boy in her class. I spent much of third year French in the corridor outside Ms Furey’s classroom, reflecting on my sins, and far too many of my lunch breaks writing “Le silence aide le travail” 100, 200 or sometimes 500 times for some transgression or other.

I wasn’t the only naughty boy in the class though and, on that particular day, I was far from the naughtiest. As I recall, on that terrible day, Martin and David were the instigators and at the peak of the mayhem most everyone in the class contributed to poor Ms Furey’s breakdown. I was, at worst, a part of the chorus, embarrassed by her tears.

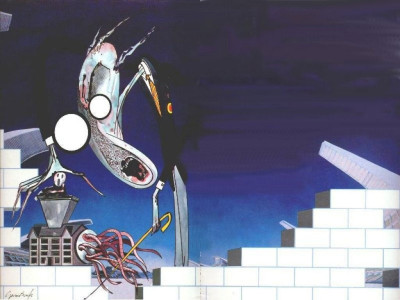

When I received my summons, I knew that evidence was not going to help my case. At roll call the next day, Mr Gooden said those dread words “Oh, and Kevin, I want to see you outside the Staff Changing Room at 12:15.” As anyone who has been on the receiving end of Mr Gooden’s wrath knows, the Staff Changing Room is where Mr Gooden kept his Size 14 Dunlop Green Flash plimsolls. The routine became depressingly more familiar with each punishment but the first time was special in its banality. First of all, the penitent (me) had to perform a series of stupid little tasks while Mr Gooden changed out of his tracksuit. Fetch me this. Bring me that. Deliver this thing. Next, you had to stare into those limpid pools of justice while he lectured you on the responsibilities and virtues required of a student at Chislehurst and Sidcup Grammar School. Finally, you had to take off your purple blazer, hang it on a coat hook and bend over to touch your toes while you waited for the Dunlop Green Flash to deliver the justice of the righteous Mr Gooden. The first whack was almost hard enough to knock me off my feet. The second and third came with increasing force as Mr Gooden got comfortable with his swing. Just three swings this time.

I forget the occasion for my second visit to the Staff Changing Room but it obviously was not sufficient because, on my third visit, the Green Flash plimsolls had been replaced by a cane and not one of those swishy canes like they used in old movies either. This was the kind of cane that the rule of thumb was apocryphally named for and each swing resulted in a thud rather than a swish leaving a welt of pink on my stinging backside. At least I was allowed to keep my trousers on.

As far as I know, Mr Gooden’s extra-curricular punishments were entirely off the record and neither the school administrators nor our parents were ever aware of them. I certainly never told my parents and would not have received any sympathy if I had. Mum had too many stories of corporal punishment of her own to be impressed by mine. I often wonder if Mr Gooden would have got in trouble if anyone in authority had known what he was up to. The closest I came to telling anyone about it was when Paul Winch and I got to enjoy some double discipline.

I forget the exact crime this time around but Paul and I were kept back after class. I was sent to wait on the landing outside room 51 while Paul went in for the opening bout of punishment. I don’t know who started shouting first but their verbal missiles were soon joined by wooden ones as they began to curse and throw chairs at each other. First Paul would scream some obscenity and throw a chair or two then Mr Gooden would shout something back and throw more chairs. This continued for an eternity while I listened in terror, knowing that I was next. Mr Berry—Head of Chemistry and Mr Gooden’s boss— walked by just at that moment and asked me why I was still in school so late and why I was crying. I told him I was about to be caned but said nothing of the roar of Bedlam that continued above our heads. Mr Berry said something vaguely soothing, grabbed his coat and headed for home. I waited for my turn in the chamber of horrors.

Eventually the ruckus died down and Mr Gooden came down the stairs to tell me to wait by his car. Paul told me later that he had broken Mr Gooden’s cane. He must not have replaced it because I never felt its bite again and Mr Gooden switched to more psychological torments. Mr Gooden drove me home that day and made me wait in the car while he spoke with my mother. I’ve no idea what he said but, when I got inside, I told my mother “I don’t want to stay at Chis & Sid”. “I know”, she replied.

Not long after the chair-throwing episode, Paul went away to some kind of prison for young offenders.. By then I was totally disengaged from school and had vowed to leave at the earliest opportunity. I never did another lick of homework or took another book home from school. In most classes, I did no work at all. No official work anyway. I read Homer under the desk in my Latin class and I wrote programs in Basic in French class. Still I came first in my class every year.

I need to explain that.

In American schools, most of one’s grade comes from the opinion of one’s teacher. In England of that era, one’s grade came entirely from how one performed in the end of year exams. End-of-year exams took three weeks and bore little resemblance to the pathetic little multiple choice tests that they do on this side of the pond. For each subject, there were two exams of three hours each. There was no “teaching to the test”, the bête-noir of American teachers. It was teach-teach-teach for most of the year then now-let’s-see-what-you-understand-you-little-fuckers.

I came first in my class at the end of the third year. I won a prize for the most improved student (last-in-class to first-in-class is hard to beat) and Mr Gooden was furious.

One of my teachers, Ms McDonnell was new to teaching and, frankly, not very good at it. She taught physics (my favorite subject) and she taught it very badly. I paid close to zero attention to her awful lessons and did less than zero of the work assigned. When the exam results were published, only two students in her class passed. I got 70% and John Burford got 57%. No one else got more than 34%. Mr Gooden made me stay in class for every break and lunch break until the end of term while I completed a year of homework that I had not done.

The last two years of Chis & Sid couldn’t pass fast enough.

I had nothing more to do with Mr Gooden but by then I had a deep seated contempt for all teachers, even the good ones like Mr Lewis. We had a Mr “Chemistry” Lewis and Mr “Biology” Lewis (AKA “Basher” Lewis). Chemistry Lewis was a genius. I’ll always remember the day that he sat in as a substitute for biology when Basher was out sick. He asked us “So what topic are you supposed to be learning today?” “Cell-division” we replied. Mr Chemistry Lewis proceeded to give the lesson on meiosis and mitosis far better than Mr Biology Lewis ever could. I really felt that I had let him down when he reviewed my chemistry exercise book and I had done only two pages of work in two years.

When ‘O’ levels came around I came equal first with three other students all of whom went to Oxford and Cambridge. But I was already out of there, headed for life in a different colour blue. In my 16 year old head, I thought that the Navy would be more of a challenge than two more years of school and ‘A’ levels.

How stupid I was.

Epilogue

I did four more years of schooling in the Navy and the exams were just appallingly, trivially easy. I even did ‘A’ level maths in my spare time just to make sure my brain had not completely rotted (it took me six weeks and I got an A). I often wonder what path my life might’ve taken if I’d gone to Cambridge instead.

Thanks Mr Gooden. You changed my life.