Fun with Guns

The first gun I ever fired was a Lee-Enfield, the mainstay of the British Empire for the first half of the 20th century and the weapon of choice of the Sea Cadets. Wikipedia says that our Lee-Enfields were modified to fire .22 rounds but, in my memory, they were the original .303s. Who knows? (Petty Officer Barker, are you out there?)

I have a bunch of medals for shooting.

Our Sea Cadet unit (TS Caprice, Bexley SCC), used to compete in tournaments pretty much every other weekend – adventure training, rifle drill, orienteering, rowing, sailing, football. We won almost every time we competed and my medal drawer overfloweth. Shooting was my forte.

I was pretty good at shooting despite the fact that I was – and still am – very short-sighted and, as a self-conscious teenager, never wore my glasses. I won silver in the South-East London shooting contest and gold in the pentathlon (shooting, orienteering, assault course, shot putt and…er … <mumble> something else I don’t remember) and best of all, we got the silver medal twice in a row in the All London Adventure Training competition (codename: Chosin; named for the Battle of Chosin in the Korean War) where we, a team of six fifteen-year-olds, were dropped in the middle of snowy nowhere for a weekend of hiking, camping, shooting and various other activities related to survival in the wilderness.

I also had an air rifle that my godfather gave me. It was already ancient when I got hold of it and the barrel was rusted. It wouldn’t shoot the little pellet thingies but I had fun chewing up bits of paper and shooting them at my dartboard. Once, I wondered whether it would hurt to shoot myself in the foot with a bit of chewed-up paper. The answer? Fuck yeah, it hurts! I got a massive blister on my big toe [One day I’ll tell you about my experiment with a super-powerful slingshot, a section of hot wheels track and a dart. Spoiler Alert: it hurt exquisitely and it took me several minutes to pull the dart out of my thumb.]

After I joined the Navy, we fired all the usual Navy weapons. Most of the time we shot the standard issue SLR (self-loading rifle) but we also fired more exotic weapons like LMGs (light-machine guns), SMGs (sub-machine guns) and, once, a 9mm Browning pistol (fun fact: a NAAFI manager with an LMG was credited with shooting down a Mirage with an LMG during the Falkland’s War).

My next gun was a twin-barrelled 30mm BMARC.

This gun was my constant companion for 6 months in 1984/85 while we sailed around and around the Falklands trying to keep the Argies from coming back. I’ve said it before, and I’ll say it again (because I love saying it), the thrill of firing that gun is something I’ll never forget.

Alarm Aircraft! Green 9-0! Elevation 2-2! Starboard guns, engage! Bang! Bang! Bang! Bang! Bang! Bang! Bang! Bang! Bang! Bang! Bang! Bang! Bang! Bang! Bang! (20 times per second).

My next gun presented a different kind of thrill. I didn’t get to pull the trigger but I did get to load it. With one shell fired every 2.4 seconds and with two little 18-year-olds – weighing not much more than the 72lb shells that the gun fired – tasked with making sure the firing ring was never empty, you can imagine how much fun it was when the Captain announced

Naval Gunfire Support! 300 rounds. Engage!

I think I still have the bruises on my collarbone from pulling those shells down from the top shelf in the magazine and catching them on my shoulder. With a range of 30,000 yards, the 4.5in Mk8 was the most powerful gun I ever fired but I fired other weapons that were bigger. OK. I didn’t actually fire a torpedo, but I fired practice shots a hundred times and I sat next to a dude who fired one from HMS Revenge. Did you know they were wire-guided? Pretty cool, eh?

I missed out on firing the biggest weapon of all, the Polaris inter-continental ballistic missile, by a few months. My submarine, HMS Revenge, fired a practice missile a few months before I joined her but we fired an uncountable multitude of water shots on my one and only patrol and, every time, I fired a practice torpedo too, the theory being that if you fire a Polaris missile, every Russian submarine within a few hundred miles will hear it and come to try to sink you.

I was the only crew member on HMS Revenge who was also a member of Greenpeace. When the Jimmy made his big speech about how everyone on board had to be totally committed to our mission, three of my messmates had to physically prevent me from going up to the control room to share my reservations about our nuclear deterrent with the captain.

[postscript: odd that my security clearance came up for review right after I joined Greenpeace].

So, despite my history with guns, nothing prepared me for the ongoing love affair that my adopted country has with weaponry of all kinds.

Everyone in the world knows how much Americans like their guns but you don’t really appreciate exactly how much they like them until you get here and talk to people. Otherwise-normal people have some really strange ideas about the appropriate role of guns in society.

The oddest idea is the one that a well-armed citizenry is the last bastion against tyranny. Even some of my most sensible friends believe that one — not just the crazies who think that Obama is a Kenyan, socialist Muslim who wants to take their guns as step one in a secret conspiracy to introduce Sharia Law and gulags. Even people who can speak in complete sentences.

Put aside, for a moment, the knowledge that the government has kept all the really good weapons for itself, the main flaw in the well-armed citizenry argument, for me, is an emotional one. When I close my eyes and try to imagine what tyranny looks like, the images that scare me the most are the ones that include well-armed citizens and which way they are pointing their guns (HINT: it’s not in the direction of the government). Think of Cambodia, Rwanda, Congo, Bosnia, Lebanon, Iraq, Afghanistan… and picture the folks holding the weapons. Were they the good guys or the bad guys? Any reason to think it might be different in a future American dystopia?

I expect that the mythology concerning well-armed militias grew from a seed of truth planted in 1776 and nurtured by 200 years of 4th-grade history. Generations of elementary school kids have been taught that the bad guys from England were repelled by the good guys using long guns hidden in their barns. Not until high school do kids learn that it’s not always so easy to tell the good guys from the bad guys.

According to Jill Lepore in The New Yorker, it wasn’t until quite recently that the Second Amendment was used to justify gun ownership.

In the two centuries following the adoption of the Bill of Rights, in 1791, no amendment received less attention in the courts than the Second, except the Third. As Adam Winkler, a constitutional-law scholar at U.C.L.A., demonstrates in a remarkably nuanced new book, “Gunfight: The Battle Over the Right to Bear Arms in America,” firearms have been regulated in the United States from the start. Laws banning the carrying of concealed weapons were passed in Kentucky and Louisiana in 1813, and other states soon followed: Indiana (1820), Tennessee and Virginia (1838), Alabama (1839), and Ohio (1859). Similar laws were passed in Texas, Florida, and Oklahoma.

The idea that the second amendment has something to do with self-defence is an even more recent innovation. A few years back, writer Jonathan Safran Foer wondered how a politician might justify gun ownership without relying on the Second Amendment.

…why, after the massacre at Virginia Tech — hours after — did Sen. John McCain proclaim, “I do believe in the constitutional right that everyone has, in the Second Amendment to the Constitution, to carry a weapon”? Just what is it, precisely, that he believes in? Is it the Constitution itself? (But surely he thinks it was wise to change the Constitution to abolish slavery, give women the vote, end Prohibition and so on?) Or is it the guns themselves that he believes in? It would be refreshing to have a politician try to defend guns without any reference to the Second Amendment, but on the merits of guns. What if, hours after the killings, McCain had stood at the podium and said instead, “Guns are good because . . . “

Why do Americans see guns as intrinsically good when the rest of the civilized world has such a different opinion?

In the rest of his article, Foer explores a few potential arguments to his rhetorical question, like public safety, a favourite among my gun-toting companions.

Guns are good because they provide the ultimate self-defense? I’m sure some people believe that having a gun at their bedside will make them safer, but they are wrong. This is not my opinion, and it’s not a political or controversial statement. It is a fact. Guns kept in the home for self-protection are 43 times more likely to kill a family member, friend or acquaintance than to kill an intruder, according to a study published in the New England Journal of Medicine. Guns on the street make us less safe. For every justifiable handgun homicide, there are more than 50 handgun murders, according to the FBI.

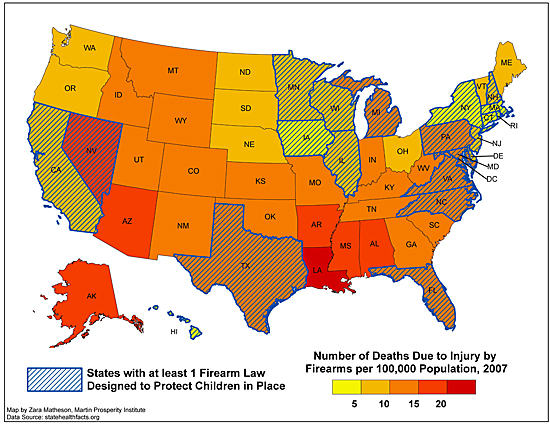

After a passionate fireside discussion with some pirates on this subject, I had occasion to look into the statistics regarding gun deaths in the USA. They really are appalling. Check out these stats summarized by NationMaster:

British Crime stats British Crime stats |  American Crime stats American Crime stats | |

| Murders with firearms | 14 | 9,369 |

| DEFINITION: | Total recorded intentional homicides committed with a firearm. Crime statistics are often better indicators of the prevalence of law enforcement and willingness to report crime, than actual prevalence. | |

| SOURCE: | The Eighth United Nations Survey on Crime Trends and the Operations of Criminal Justice Systems (2002) (United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, Centre for International Crime Prevention) | |

| Ranked 29th. | Ranked 1st. 668 times more than United Kingdom | |

| Murders committed by youths | 139 | 8,226 |

| DEFINITION: | Homicide rates among youths aged 10–29 years by country or area: most recent year available (variable 1990–1999). | |

| SOURCE: | World Health Organization: World report on violence and health, 2002 |

The numbers are even more appalling when you factor in accidental deaths.

In 2004, more preschoolers were killed by firearms than law enforcement officers, according to the Children’s Defense Fund. The number of children killed by guns in the United States each year is about three times greater than the number of servicemen and women killed annually in Iraq and Afghanistan. In fact, more children — children– have been killed by guns in the past 25 years than the total number of American fatalities in all wars of the past five decades.

There are several theories for why America is the most violent country in the developed world. The most compelling is that democracy came too early to America. Steven Pinker’s Better Angels of our Nature points to the state monopoly on violence as a major contributor to the persistent and dramatic decline in violence over the last several thousand years.

The central thesis of “Better Angels” is that our era is less violent, less cruel and more peaceful than any previous period of human existence. The decline in violence holds for violence in the family, in neighborhoods, between tribes and between states. People living now are less likely to meet a violent death, or to suffer from violence or cruelty at the hands of others, than people living in any previous century.

Book review of Pinker’s Better Angels of our Nature in the New York Times.

Pinker documents in excruciating detail just how much more peaceful our century is than previous ones (if like me, you are wondering how Pinker explains away the Holocaust and World War I, go read the book. It will answer all your questions, I promise).

One of the reasons for the decline in violence, as Pinker describes in this article, Why are States so Red and Blue, is that

All societies must deal with the dilemma famously pointed out by Hobbes: in the absence of government, people are tempted to attack one another out of greed, fear and vengeance. European societies, over the centuries, solved this problem as their kings imposed law and order on a medieval patchwork of fiefs ravaged by feuding knights. The happy result was a thirty-fivefold reduction in their homicide rate from the Middle Ages to the present. Once the monarchs pacified the people, the people then had to rein in the monarchs, who had been keeping the peace with arbitrary edicts and gruesome public torture-executions. Beginning in the Age of Reason and the Enlightenment, governments were forced to implement democratic procedures, humanitarian reforms and the protection of human rights.

In America, the sequence of events was slightly different.

The historian Pieter Spierenburg has suggested that “democracy came too soon to America,” namely, before the government had disarmed its citizens. Since American governance was more or less democratic from the start, the people could choose not to cede to it the safeguarding of their personal safety but to keep it as their prerogative. The unhappy result of this vigilante justice is that American homicide rates are far higher than those of Europe, and those of the South higher than those of the North.

How much higher?

Quoting Democracy in America at The Economist,

Murder rates are about four times higher in America than in western Europe. And guns are not the only reason; murder by stabbing and clubbing is higher, too. The murder rate is higher among blacks, but American whites are more violent than European whites. The South is America’s most violent region; both blacks and whites in the South are more violent than those in the northeast. In other words, the murder rate is highest in those states that most disdain the sovereign (“government”) and champion self-reliance.

The outlook isn’t all bad though. Even though it seems like liberal politicians are getting ever more cowardly about gun control as the NRA gets ever more powerful, rates of gun ownership are actually falling…

The United States is the country with the highest rate of civilian gun ownership in the world. (The second highest is Yemen, where the rate is nevertheless only half that of the U.S.) No civilian population is more powerfully armed. Most Americans do not, however, own guns, because three-quarters of people with guns own two or more. According to the General Social Survey, conducted by the National Policy Opinion Center at the University of Chicago, the prevalence of gun ownership has declined steadily in the past few decades. In 1973, there were guns in roughly one in two households in the United States; in 2010, one in three. In 1980, nearly one in three Americans owned a gun; in 2010, that figure had dropped to one in five.

… and the opinions of gun-owners are diverging from the hard-line positions championed by the NRA.

Gun owners may be more supportive of gun-safety regulations than is the leadership of the N.R.A. According to a 2009 Luntz poll, for instance, requiring mandatory background checks on all purchasers at gun shows is favored not only by eighty-five per cent of gun owners who are not members of the N.R.A. but also by sixty-nine per cent of gun owners who are.

It’ll take a while but I am confident that Americans will eventually succumb to the same civilizing influences that have tamed Europeans’ violent urges.

Every country has, along with its core civilities and traditions, some kind of inner madness, a belief so irrational that even death and destruction cannot alter it. In Europe not long ago it was the belief that the “honor” of the nation was so important that any insult to it had to be avenged by millions of lives. In America, it has been, for so long now, the belief that guns designed to kill people indifferently and in great numbers can be widely available and not have it end with people being killed, indifferently and in great numbers.

I expect that, part of the solution – the transition to a society with fewer guns, will result from the recognition that the second amendment, like all the other amendments, has limits.

From the Supreme Court’s judgment in District of Columbia vs Heller, written by Justice Scalia:

Like most rights, the Second Amendment right is not unlimited. It is not a right to keep and carry any weapon whatsoever in any manner whatsoever and for whatever purpose: For example, concealed weapons prohibitions have been upheld under the Amendment or state analogues. The Court’s opinion should not be taken to cast doubt on longstanding prohibitions on the possession of firearms by felons and the mentally ill, or laws forbidding the carrying of firearms in sensitive places such as schools and government buildings, or laws imposing conditions and qualifications on the commercial sale of arms. Miller’s holding that the sorts of weapons protected are those “in common use at the time” finds support in the historical tradition of prohibiting the carrying of dangerous and unusual weapons.