A Beautiful Mind

Whenever we hear a story about someone who has suffered a tragedy or illness that leaves them in a bad way physically, we have that conversation. The one that goes “I wouldn’t want to live that way. Just have me put down.” I have a different response: as long as I can still think, I will want to go on.

And if I can’t think? I’ll go on anyway because a) I have nothing to lose (I can’t think, remember?) and 2) How do you know I can’t think? Maybe I really can think but just can’t communicate what I am thinking.

I expect the state of Ebert’s face leaves a lot of people thinking “I wouldn’t want to live like that” but those people are missing the most beautiful part of Roger Ebert. He is absolutely one of the most powerful writers on the planet and I feel privileged that I can read his blog every now and again (but cheated that I only discovered it in the last couple of years).

Even when Ebert is writing about something as trivial as a movie, his words are magnificent but he rarely stays on topic long enough to merit the lowly title of movie critic. More often he writes about himself – which is to say, he writes about me. He wields his pen like a time machine transporting me magically into my memories. To memories of burning shame – or burning pride – or of quiet moments of reflection that repeat, reprise and return.

Today, Ebert started with the madness in Arizona but he was soon telling me about that time a bunch of midshipmen from Dartmouth drove down to Torquay with our consorts from Stover Girls School – me with the blackest girl i ever kissed – and reminding me how it’s a mistake, if your grass skirt is homemade, to go commando.

But his important topic for today was how the deepest lesson you must learn, as you metamorphose from child to man, is to learn to imagine what it is like to be someone else.

Ebert’s example, as always, is mine.

That brings me back around to the story of the school mural. I began up above by imagining I was a student in Prescott, Arizona, with my face being painted over. That was easy for me. What I cannot imagine is what it would be like to be one of those people driving past in their cars day after day and screaming hateful things out of the window. How do you get to that place in your life?

I often wondered, seeing pictures of those brave first students who calmly smashed through the racial barricades in Little Rock, what was it like to be those people?

Not Elizabeth Eckford. It’s easy to imagine being her – just like it’s easy to imagine being Neil Armstrong making his giant leap for mankind, or Geoff Hurst making sure it really is all over now.

What was it like to be the girl behind her with so much hatred for someone she does not even know?

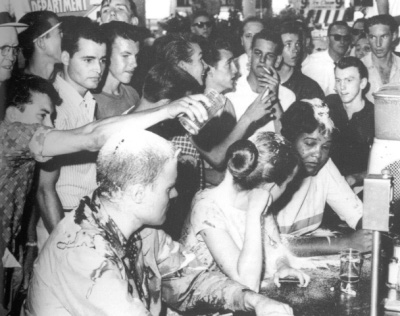

What was it like to be that guy who was so offended by the idea of black people and white people eating lunch together that he poured his drink over them?

What is it like to be so afraid of catholic school children walking on protestant streets that you need to throw bricks at them?

Ebert:

But what about the people in those cars? They don’t breathe that air. They don’t think of the feelings of the kids on the mural. They don’t like those kids in the school. It’s not as if they have reasons. They simply hate. Why would they do that? What have they shut down inside? Why do they resent the rights of others? Our rights must come first before our fears. And our rights are their rights, whoever “they” are.

Ebert’s story starts with the town in Arizona that commissioned a mural for their elementary school and then made the artist lighten the faces after a local politician complained on the radio. It ends long ago with a story from his own life.

One day in high school study hall, a Negro girl walked in who had dyed her hair a lighter brown. Laughter spread through the room. We had never, ever, seen that done before. It was unexpected, a surprise, and our laughter was partly an expression of nervousness and uncertainty. I don’t think we wanted to be cruel. But we had our ideas about Negroes, and her hair didn’t fit. Think of her. She wanted to try her hair a lighter brown, and perhaps her mother and sisters helped her, and she was told she looked pretty, and then she went to school and we laughed at her. I wonder if she has ever forgotten that day. God damn it, how did we make her feel? We have to make this country a place where no one needs to feel that way.

John Newcaso was the first black kid I knew and I am happy to count him among my 7 year old friends. If my memory serves me, John was an orphan and newly arrived from Africa. He was very popular, perhaps because he was the only one who could throw two punches in a second—Hey! We were seven!—or because he held the record for longest flight for a paper aeroplane even after we all copied his design. But we made fun of him because he wore a brace on his legs.

I wonder how he remembers us?

Was his first year in cold, dreary England tremendous fun because he had so many friends and lashings and lashings of ginger beer? Or hell because of our relentless teasing? Or maybe it was just my memory cleaning up the darker corners? I hope not.