Travels across Thailand

— 1989 —

Civilised Singapore was a bit of a shock after the wilds of Indonesia.

I got the train into the centre of Singapore, and a man at the station gathered up the poor travellers like me and gave us a floor to sleep on. I shared the floor with five or six other travellers. I didn’t get around much, except for a bit of shopping, and I had my first shower in months. I visited the Raffles Hotel for my birthday, but it was closed for renovations, so after a few days in Singapore, I got the bus to Malacca.

Malaysia was lovely too, and also very civilised. I enjoyed Kuala Lumpur and all the little villages. The Cameron Highlands were delightful: like having afternoon tea in the British Empire in 1907. On my train ride to Penang, the train was full, so I sat on the coupling between two carriages with a bunch of Malaysians. We sang through the night with guitars and lots of wine, and with our legs dangling down.

Malaysia was charming from start to finish, but not much to write a blog post about, so I had a mussaman curry in Penang, then got the bus to Thailand.

Hat Yai was a bit of a shock because Thailand was the first country where I didn’t speak the language, and no one spoke mine. I had never been to a Thai restaurant, and had no idea what Thai people ate. I finally managed some Pad Thai, then got a bus to Krabi and a ferry to Ko Phi Phi.

Ko Phi Phi is lovely beyond words. I met an Australian and a Californian on the ferry, and we agreed to share a chalet, then walked along the beach to find one. The first few were posh chalets for rich people, but as you got further along the beach, they became more like huts made of bamboo for poor people. But there was no room at the inn until the very last one: a shed with a single bed, so my new traveller friends and I put our backpacks in the shed, and we slept on the beach.

We had a wonderful time on Ko Phi Phi. My new friend from Sacramento had been in a circus back home, and he taught us to juggle and to loose rope walk (like tight rope walking, but looser). We swam lots in the Andaman Sea, and we drank lots of Mekhong Whiskey. I can still juggle and do all the tricks, and I still love Mekhong Whiskey.

The bus to the other side of Thailand was full, so I had to stand on the step on the outside of the bus, and hang on with one hand. There were four of us on the step, but no guitars this time.

Koh Samui was the first place I visited that was designed for fun times. There were only a few resorts and no airports, so hardly any proper tourists made it there. Just us backpackers. The beaches were gorgeous, the restaurants were delicious, and the nightclub was exciting.

I was at the nightclub one night with an American friend, Mark, and, after the ladyboy show, it was time to dance. Mark asked me to be his wingman when he made a move on one of the beautiful Thai women at the next table. Mark didn’t get very far with his romantic endeavours, but I became very good friends with a Cambodian woman named Noi. Noi kind of adopted me, and took me to places that tourists didn’t usually go. Noi lived in a house with those Thai women, and I spent many evenings with them. They cooked me dinner, and I helped them write letters to older European ‘boyfriends’, encouraging them to send lots and lots of money.

I enjoyed my time with Noi, but it was eventually time to move on, and I headed for Bangkok. The bus to Bangkok was full, though, so I had to stand on the step on the outside of the bus and hang on with one hand. There were four of us on the step, but no guitars this time.

Backpackers in Bangkok always stay on the Khao San Road, and a dozen backpackers shared the linoleum floor in the 40°C heat. Bangkok is an extraordinary city. The tuk-tuks, the massage parlours and the women doing tricks with ping pong balls are services you don’t find in other cities. There was one lady on the Pat Pong Road who stuck a marker pen in her lady parts, then wiggled her hips around over a sheet of card. When she was done, she held up the card, and it said “Welcome to Bangkok.”

Bangkok is a great base for seeing the rest of the country, and my first trip was to Kanchanaburi. The train looked like it was made in 1920, with wooden benches and no glass in the windows, and at each station, the carriage filled up with twenty women selling bowls of chicken, pad thai, and cups of green tea.

We chugged along for a couple of hours, but all the signs were in Thai, so I had to look for a town with a long name written in squiggles, and — hey presto! — I was in Kanchanaburi.

Kanchanaburi was wonderful. I walked down the hill to the River Kwai, where a collection of cabins floated on the river. Every morning, I woke up and dived straight into the river, then swam back for breakfast. I made friends with a gang of Thai students, and they invited me on a bus ride out to Three Pagoda Pass, on the border with Burma. It was a couple of hundred miles away, but we stopped every now and again at Buddhist temples, where they treated us as special guests.

Three Pagoda Pass has been the main route into Burma from Siam for hundreds of years and has been the scene of many a battle. It was the scene of a battle the day before we got there, too, and there were machine gun holes in the walls. We got lucky, I guess. After we snuck across the border into Burma, we were in the poorest village you can imagine. The children were barely clothed and looked like they had not eaten for days. It was all very sad.

Back to Kanchaniburi, then back to Bangkok, then off to Chiang Mai.

Chiang Mai was just another city, but Chiang Rai was only a little further, and there were goats and cattle walking down the streets.

I was in a café in Chiang Rai one morning, hanging out with a Kiwi and a pair of Danish girls, when a Shan tribesman came and asked if anyone wanted to go for a trek into the Shan Hills, in the forest between Burma and Thailand.

‘Sure!’, we said.

This was one of the highlights of my adventure.

We got off the bus in a tiny market on the border with Burma. Our guide bought some rice and some vegetables, then we set off into the forests and the hills.

The Burmese hills are populated by a diversity of tribes — Shan, Karen, Hmong and Akha — and we spent each night with a different tribe, with our first night in a Shan village. The Shan were a slash-and-burn tribe who stayed in a village for a few months, then wandered off and burned down a new area of forest to make their next village. The huts were sparse — just bamboo walls with a ceiling and a floor. There was no electricity (of course), and no light after 6 pm. We slept on the bare wooden floor.

Our guide recruited a Shan tribesman to carry our stuff for us. We didn’t have a lot of stuff since we’d left our backpacks back in Chiang Rai. We just had a pot to cook our lunch, and each village gave us something to eat. Every time we stopped for a drink of water or lunch, our guide had a cigarette, and our porter bubbled up his opium pipe. He offered us a hit every time, but we’d decided ahead of time that we weren’t going to do drugs, and we declined.

I think we were the only backpackers in every café in all of Thailand who weren’t doing drugs. Opium, hash, and heroin. Cocaine and LSD. I don’t know why I decided not to do drugs, but I am very glad I did. Someone in that forest, in the group behind us, overdosed on opium and had to be rushed down to Chiang Rai, which was a day’s trek away.

On one pleasant afternoon, we spotted a beehive up in a tree, and our guide tried to dislodge it so we could have some delicious honey for our lunch. The bees, though, objected to our assault on their hive. We still got our delicious honey, but we also got covered in a lot of bee stings.

For my previous several months in Southeast Asia, I had worn espadrilles in the cities and walked barefoot out in the countryside. After a couple of days of trekking through the forest, we were walking down a hill covered in sharp rocks, so I thought it best to put on my espadrilles. But…! ‘Oops!’ I had lost an espadrille! I made myself some shoes out of banana leaves, but they didn’t do a lot of good, and I trekked the next couple of dozen miles barefoot.

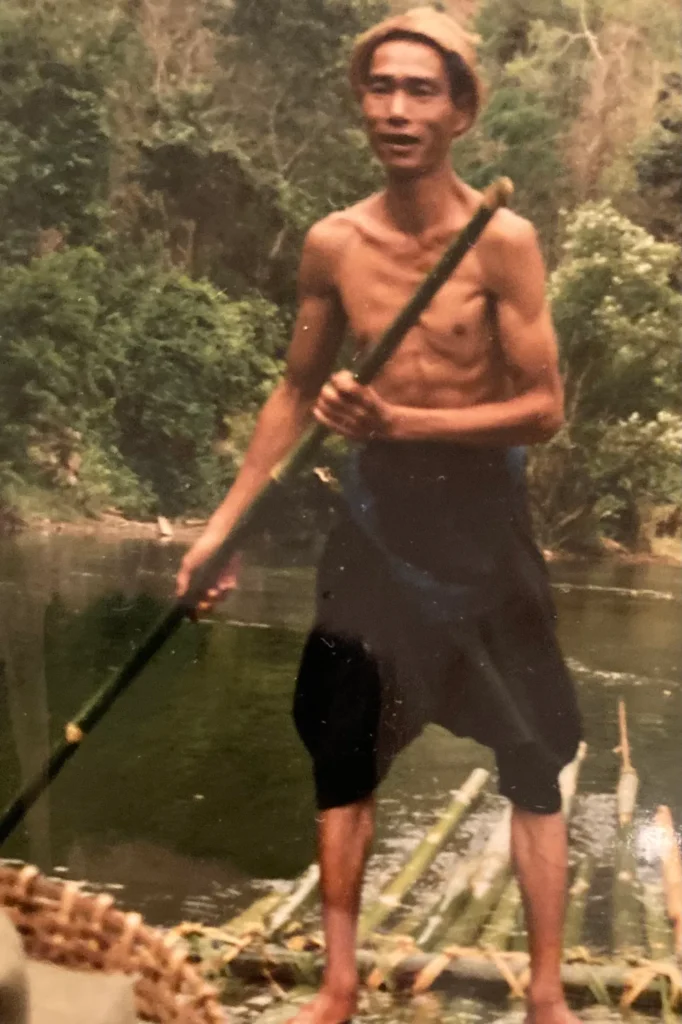

The grand finale of our trek was a stroll down to a nearby river where they made us a bamboo raft. We floated down the river for several hours before climbing up onto a couple of elephants for the rest of the journey to the last Karen village. This village was a bit more developed than the others we’d stayed in, but it was still made from bamboo. There was still no electricity, but they had a clever little water channel that carried water down into the village.

We hadn’t washed for days, so our lovely two Danish girls thought it would be an awesome idea to take all their clothes off and wash themselves under the water channel. The Kiwi and I were horrified! What if the villagers got angry that we had just wasted all their clean water? What if they were offended by our nudity and executed us??

Danish women have different rules.

We managed to get the girls’ clothes back on, and our guide led us down to a delightful little pool with a waterfall — just like Gollum’s Pool in The Lord of the Rings — where we could all get naked without being murdered.

After our most memorable hike, we walked back to Chiang Rai, then I caught the bus back to Bangkok. In Bangkok, I had the glimmering of a wish to fly to India and explore some more, but after a year of travelling, I was a little homesick, and I decided to head for home. I still had a week before my flight, though, so I headed back down to Koh Samui to say goodbye to Noi, and I read The Grapes of Wrath, and I drank lots of Singha beer.

I was very sad to end the greatest adventure of my life, but I was looking forward to seeing my family back in England, and even the explosive intestines that I acquired in Karachi didn’t trouble me too much.

A train ride from Heathrow took me back to my sister’s house in Sidcup, and I waited patiently for her to come home from work. Of course, she didn’t recognise me with my long blond hair in a ponytail and my dark brown skin, so it took a bit of friendly banter to persuade her that I was her brother.

Anyway. After a year of travelling, I was home.