The Church in England

I was listening to a discussion yesterday between Ross Douthat (Catholic) and Doug Wilson (Evangelical, Calvinist), and Wilson advocated for a Christian Nationalism in America, where everyone does their best to conform to the moral laws in the bible, and the country’s laws are restructured to reflect those laws. He thinks America began as a Christian nation and should become one again.

Wilson’s ideas about Christian morals are a bit more extreme than anything I’ve come across in real life. He’s against all the obvious things, of course: abortion, sodomy, and no-fault divorce. Teaching Christianity in schools should be allowed. Teaching trans ideology should not. But he goes way beyond this.

The laws in the Old Testament will become the laws of America. Men will cast votes on behalf of their wives. Feminists will have no say in the law. Wilson says that America got along OK with Jews for a long time, and America can get on with people of other religions, too, but they’ll have to follow the Old Testament Laws, and minarets will not be allowed — and definitely no building 90-foot statues of Lord Hanuman.

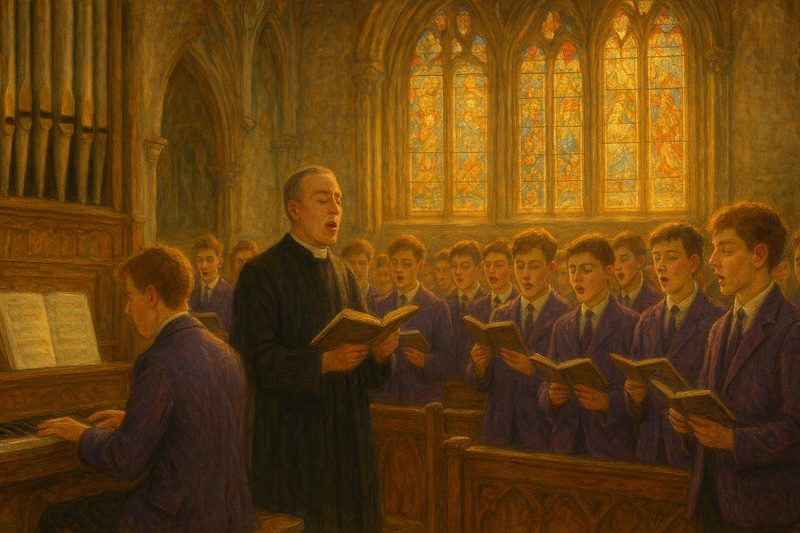

When I was at school in England in the 1970s, we said the Lord’s Prayer every morning, and sang ‘What a friend we have in Jesus!’ We were taught religious education once a week and everyone went to church at Christmas and Easter.

We were brought up in the Church of England, the official church of my country. The small handful of Catholics were allowed to opt out of morning prayers and religious education. Atheists were allowed to opt out, too, but none of us did. The praying and the churching were just things we did, even though (almost) none of us believed in God.

Religion in English schools was very different to American schools. The 1944 Education Act required that every day ‘shall begin with collective worship’ and ‘religious instruction shall be given’ in every school. Parents were allowed to opt out, but almost none did because it would have meant their children being separated from their friends. We learned together.

Said Judas to Mary ‘Oh, what will you do?’

With your ointment so rich and so rare?

I’ll pour it all over the feet of the Lord,

And I’ll wipe it away with my hair.

For most of the last century, England had the Christian Nationalism that Doug Wilson wished for, even if our laws were more forgiving than Old Testament laws. And there were definitely no minarets or statues of Lord Hanuman.

In life, too, we were all baptised, married and buried by the Church of England; families said grace over their Sunday dinner and sent Christmas cards with angels on them, or the baby Jesus. We all got to play shepherds in the nativity play.

That’s almost all gone now.

The number of weddings in the Anglican Church has fallen from 166,000 in 1970 to 8,000 in 2020, and morning prayer in school doesn’t happen; not because of atheists, but for fear of offending students of other religions.

The Church of England is still the official church, but hardly anyone pays it any attention anymore.

With this ring I thee wed, with my body I thee worship,

and with all my worldly goods I thee endow:

In the Name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Ghost.

Amen.

The idea of a society built around Christianity has been at the centre of English culture for five hundred years. The Church of England broke away from the Catholic Church to satisfy King Henry VIII’s desire to change wives, but one of the advantages of its independence has been the freedom to move with the times, while Catholics still have to do what the pope says, which is the same as what the pope said five hundred years ago. This gives England the freedom to update our laws — and our church — to change with the culture.

Unlike some other churches, the Church of England allows a breadth of opinions, and as Humanists UK said recently, ‘The UK was long a society where religion was worn lightly by the vast majority.’ This liberal attitude to religion supports devout worshippers, while also welcoming people who go to church because it’s part of their culture. The Church of England offers a culture that can be shared by Christians and atheists alike.

The Church of England left room for other religions, too. In my childhood, that meant allowing Catholics to skip the morning assembly. But these accommodations became less practical as the number of people from other faiths increased.

To take one small example, offering halal options at school lunches is feasible, but what happens when the majority of students are Muslims? Should we switch over to halal for everyone? What happens to the morning assembly when most children are not Christian? Do we still say the Lord’s Prayer?

When a majority of the population comes from elsewhere, English culture will lose its significance.

And that will be England gone,

The shadows, the meadows, the lanes,

The guildhalls, the carved choirs.

There’ll be books; it will linger on

In galleries; but all that remains

For us will be concrete and tyres.

Going, Going — Phillip Larkin

This fading of English culture is what the people marching with their flags of St George are afraid of. Multiculturism has brought us many festivals to appreciate, like the Notting Hill carnival and Eid al-Fitr at the end of Ramadan — and who doesn’t love a lamb vindaloo? But what happens when English culture is eclipsed by these other traditions?

We can pretend those protests are about racism — and, surely, there are plenty of racists protesting too — but the vast majority of protesters are mourning the slow loss of their culture, and race has little to do with that. Counter-protesters like to claim that the Flag of St George is used to intimidate people of other ethnicities, but England’s flag is not racist; it’s a symbol of our history.

What will happen to English culture when most families no longer share our history? Will parents still teach English myths and legends to their children? How many will remember Lady Godiva riding naked, or remember the love affair between Sir Lancelot and Queen Guinevere? Will King Alfred and Lord Nelson still be our heroes?

Who will remember English folk songs?

Fifty years from now Britain will still be the country of long shadows on county grounds, warm beer, invincible green suburbs, dog lovers and pools fillers and – as George Orwell said – “old maids bicycling to Holy Communion through the morning mist and if we get our way – Shakespeare still read even in school.”

— John Major

Do we still believe this to be true?

Culture changes with time. This has always been so. Peasants became factory workers, and food was mass-produced after the Industrial Revolution. Shakespeare never even tasted fish and chips. But those changes happened over decades and centuries. Culture changes faster when there are one million new immigrants every year, and when more people watch YouTube than read books. It’s changing faster than ever now.

It was only fifty years ago that the Church of England was a big part of our lives, but the culture of my childhood is fading away. I complained when we said our prayers every morning, but now I mourn the slow loss of our culture.

“I’m kind of grateful to the Anglican tradition for its benign tolerance… I suppose I’m a cultural Anglican and I see evensong in a country church through much the same eyes as I see a village cricket match on the village green. I have a certain love for it.”

― Richard Dawkins